What Five Actions Would Real Resiliency Address?

April 20, 2018

Reliability has long been associated with the power sector and is, in fact, one of the cornerstones of the modern electric grid. Defined broadly as a utility’s ability to supply as much power as is needed at any given time, it is encoded in standards at every level, from NERC to state regulatory commissions. Significantly, these standards are quantitatively backed, enabling outcomes to be analyzed in detail to identify problems and ensure that expensive solutions to edge case scenarios are not over applied.

In contrast to reliability, resiliency, the measure of how quickly a power system can recover from catastrophe, is a new term to most of the power sector. It came to prominence only in late 2017 when it played a key part in the ill-fated Department of Energy Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NoPR). This measure proposed guaranteeing a profit to certain power plants capable of storing fuel onsite on the basis that they increased the speed with which the power system could recover from a catastrophic event.

While FERC ultimately failed to approve the NoPR, it did start a conversation within the industry of how to value resiliency. This was likely bolstered by the recent hurricane season in which both Houston, Texas and San Juan, Puerto Rico experienced massive power outages but came back online at vastly different rates. What the NoPR did not do, however, was provide a framework for how to talk about resiliency. Complicating this even more was the NoPR’s assumption that resiliency is derived through fuel stockpiles rather than transmission infrastructure, as transmission outages are by far the most common cause of outages.

In the weeks after FERC’s NoPR ruling, “resiliency” became something of a movable feast as industry and lobbying groups each sought to explain how their generation technology was vital for system recovery. Noticeably missing from this first wave of comments were the individual grid operators and groups that were less aligned with industries and more tied to the overall security of the power system. Also missing from many resiliency conversations was an acknowledgment that a) grid recovery was about more than just generation and b) many aspects of resiliency were already baked into existing markets.

With both President Trump and Energy Secretary Perry now stating that they would like to see action taken in the name of resiliency, it is worth thinking of what real resiliency would address.

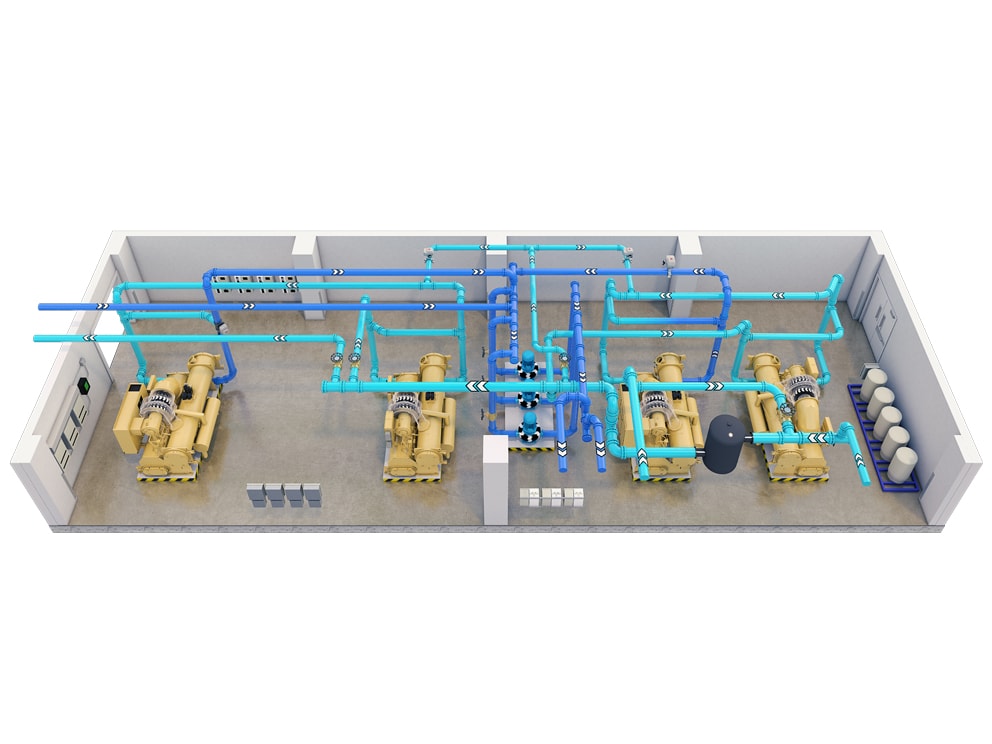

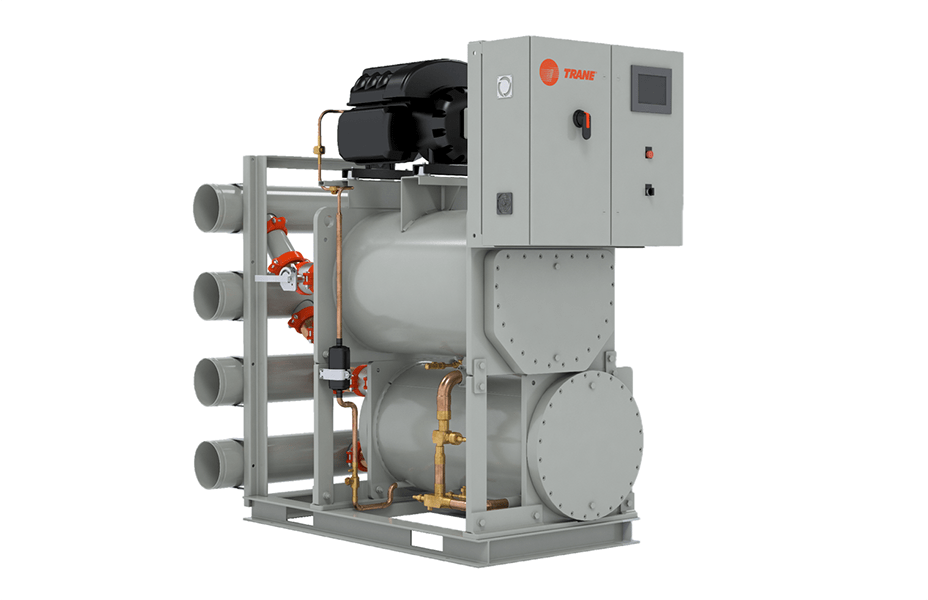

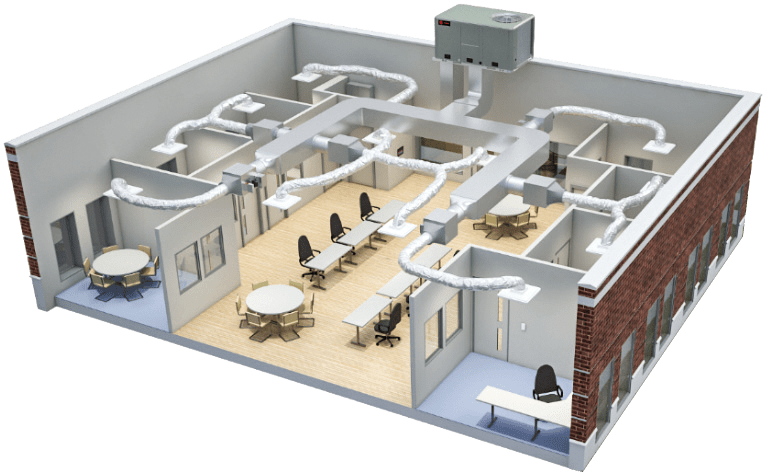

- Most outages are caused not by generation but through the transmission and distribution systems. Centralized generation is, at best, a second-tier solution to resiliency, though distributed generation can go far in allowing an individual building to function normally, and even act as a grid asset, in adverse conditions.

- All generating fuels have their own transportation systems and typically the more robust this system is, the less efficient the fuel is for power generation. Fuel oil and gasoline have the most established distribution systems, but are the least efficient for generation. Natural gas distribution is susceptible to interruption in times of cold weather, but costs less per megawatt hour. Coal falls somewhere in between.

- All generation technologies have strengths and weakness; to say one is unequivocally better or worse than another is to overly simplify a complex situation. In times of extreme cold, for example, coal units become less effective due to the coal itself freezing, while natural gas faces competition from heating demand. At the same time, solar generation is least effective in the winter while wind also produces less power January through March. The best solution is usually not the same for everyone.

- Markets matter. In general, mechanisms that send price signals to producers are more cost effective, though more complex, than simple make-whole payments or the fiat development of generation, as they will come into play only when needed.

- Analytical measures are important. Solutions should have associated metrics that will give indicators that a policy is or is not successful, or is being overused. This will help to ensure that any action is effective while also minimizing costs.

These factors do not point to a simple solution. Power markets are complex and varied in their fuel costs, environmental factors, demand needs, and existing investments in generation, transmission, and distribution. Additionally, grid operators are answerable to the priorities of those to whom the power is served through local elections and legislative actions. For this reason, standards on reliability tend to vary from location to location, with regulators mostly ensuring that standards are spelled out and adhered to. It stands to reason the resiliency would be an equally individual property, and should be handled in a similar fashion.