Federal Tax Cuts Could Mean Power Savings for End Users

January 12, 2018

Summary

With the signing of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, many state Public Utility Commissions (PUC) are now looking at how the bill will affect the utilities that they regulate. At the heart of the Act is a substantial decrease in the corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%, effectively lowering the cost of doing business for regulated utilities. Since tax burdens are typically rate-based, meaning that they are passed through to a utility’s customers, most utility customers should be able to expect their rates to go down.

There is, a catch, however. Corporate taxes are taken into account when utility rates are set but in most circumstances these rates must be adjusted by regulators when tax rates are altered. Typically, this is not a major issue, because legislation such as this Act typically takes effect months after signing. With the 2017 bill, however, this is not the case.

For this reason, many state regulators are rushing to implement some type of regulatory reform prior to March, when customers will begin overpaying under most regulatory systems. These actions have ranged from simply directing the utilities to document their costs to actually initiating rate cases. In some states, such as Kentucky, industry groups like the Kentucky Industrial Utility Consumers have filed complaints with the PUC trying to speed the process.

Analysis – A Similar Situation

Functionally, this tax bill is similar to one passed in 1986 that saw corporate tax rates drop from 46% to 34%. It is difficult, however, to determine if customers actually saw their total bills decrease because of the reduction in corporate tax rate.

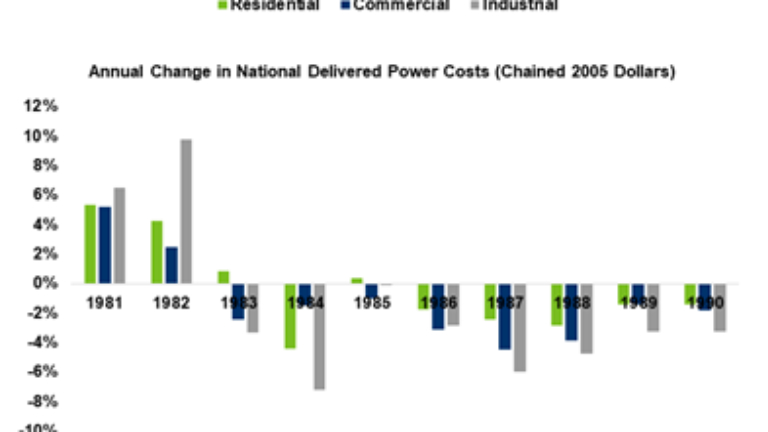

Three conclusions can be drawn from the charts illustrated here. First, the early-1980s was a difficult time in U.S. monetary policy. The differences between the real and nominal charts indicate more volatility than we are used to seeing today. For example, in 1987, residential customers saw their power costs increased by nearly one half of a percent, though this amounted to a 2.5% decrease in costs when inflation is removed. This volatility makes drawing hard numbers from this data rather difficult.

Second, from looking at the real chart, we can see that while power costs did decrease in the year after the 1986 bill was signed, they did not do so in a way that was especially unique for the time. In fact, aside from a few exceptions, power costs across all sectors decreased dramatically and consistently from 1983–1990.

Lastly and most significantly, industrial users tend to be on the cutting edge of any rate-changes, usually seeing the largest decreases/increases in their cost of power. This is not accidental, but rather a feature of the ratemaking process, wherein residential customers are often sheltered from price increases at the expense of being unable to take advantage of many cost decreases. Commercial rates typically lie somewhere in middle.

Conclusion

In summary, while it is clear that regulators across the country are attempting to start processes that will lower power rates for regulated customers, it is unclear how much end-users will benefit. What is clear, however, is that while these rate cuts will most likely be seen across all sectors, they will most likely be concentrated with industrial customers. It is also unknown if states that have experimented with performance-based ratemaking will now seize this as an opportunity to do so. Current power prices in most parts of the country are not seen as too burdensome, and rather than directing the saved money toward end-users, moving savings toward reliability and resilience projects is also a distinct possibility.